We are living in an era where the lines between the Bourgeoisie and the Bohemians are becoming blurred. With the advent of the information age, we can now curate more aspects of our individual lives from our online preferences to our social behaviors. This is the coming tide, where intellectual properties like music, films and scientific patents are now as valuable as steel, copper and aluminum. This is the coming storm caused by digitization and entrepreneurship that disrupts the standard ways of creative expression. This is the rise of the casual creative.

Casualization refers to an increasingly common work arrangement where employees work on a project-by-project basis, rather than as year-round full-time employees. This trend is becoming the norm in workplaces across the world and within our creative industries. Just as casualization is reaching the workplace, so is creativity. According the U.S. Department of Labor, creative and service sector jobs are growing while blue-collar physical jobs are in dramatic decline (Florida, 2012). As many people transition through jobs (approximately every 2-3 years) there is an increase in cultural participation. Whether it is reading novels, writing haiku poetry, or thinking of out-of-the-box solutions on a factory floor, creativity is a condition of employment and many teams are forced to find creative solutions to increase productivity, and performance. As the casual creative continues to evolve, the engaged consumer is becoming more participatory and this can lead to an incredible output of content and new businesses that were unthinkable decades before.

It may be that our economy has created opportunities for passion to outweigh profit in a world where producers and consumers can develop their skills and become professional hobbyists. This trend is further defined by David Brooks in his book Bobo in Paradise. He details that “Bourgeois Bohemians” (or “Bobos”) are a subset of the population that has morphed the yuppie businessman with the entrepreneurial artist. Much of his argument exposes a contrast between the Protestant work ethic and the artist’s Bohemian tendencies (Brooks, 2002).

One example of a famous casual creative is former President George W. Bush. After leading our country through the dot-com boom, the attacks on 9/11, and the war in Iraq, he regained his celebrity status outside of his work in politics in the years to follow. In January of 2009, George W. Bush left the office of the President of the United States and returned to his ranch in Crawford, Texas. Like many former Presidents, he was welcomed by a handsome six-figure pension, a new home and most importantly a career of his choosing. While many Presidents chose to open foundations, build houses, and increase awareness on certain political issues, he focused his efforts on a new passion: painting.

Many people believed that this career move was confusing, while others went on to support his new choice. Quickly his paintings surpassed the level of an amateur leading Bush to publish a book of his own work entitled Portraits of Courage (Kennicott 2017). Now, Bush’s portraits of military personnel and veterans have been a best seller in stores across the nation. You can see that although his skill is primitive, his intention and expression is profound. Accented by color, contrast and contour, it is clear to see that his skill has developed substantially since leaving Washington D.C. George W. Bush in his later years is a great personification of Dave Brooks’ Bobo phenomenon as he transitions away from the presidency towards a passion for painting.

Figure 1. George W. Bush’s Vladamir Putin (Bush, 2017)

Richard Florida describes this same phenomenon as “The Big Morph” detailing the resolution of centuries-old tensions between standardization and differentiation within the working and creative classes. He would argue that Bush’s development as a painter is similar to millions of other creatives living around the world. In Florida’s book The Rise of the Creative Class, he predicts the future of the creative class and the work that they will accomplish in the years to come. His argument outlines a shift from “survival” to “self-expression” values. These values of self-expression were extensively documented in the Post-Fordist era of the 1960s and 1970s when our country celebrated our creative ideas over our industry.

However, what happens when ideas and creativity become tradable commodities? When basic resources transition from production to ideation, materials and labor may soon carry less weight than ideas and knowledge in our future economy (Florida, 2012). Florida’s theory about this crucial transition is criticized by scholars, but one fact does remain true; work is changing in America and jobs are transitioning to the creative class (as seen in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Work trends over time in America 1800-2010 (Florida, 2012)

The creative class, according to Florida, values individuality, meritocracy, diversity and openness. One example seen in our daily lives is karaoke. In most karaoke bars you risk embarrassment by putting yourself in front of a crowd of your peers. After performing, the crowd applauds you based on your individual song choice, and shows you respect for your performance regardless of how talented you are. Cultural moments like this can be found in other forms as well; including “paint-and-sip” classes (Carrns, 2017), and “dad-rock” bands (Cohen, 2017) that allow people to exercise their ability to create artwork in an incredibly low stress environment. “Creativity is multidimensional and experiential,” according to Florida, requiring self-assurance along with an ability to synthesize and take risks.

This cultural shift, led by the creative class, could be changing our institutions along with our channels for distribution. People are producing their own preferred content on new platforms and sharing it with their closest friends instead of engaging with traditional high-brow work. Because large cultural institutions are not adapting to the wisdom of crowds (Watts, 2011), they are unfortunately forced to lay off many below the line staff whose salaries fail to meet their bottom line. For every George W. Bush there are hundreds of professional visual artists, dancers, and musicians who are losing work and opportunities due to the changes in the industry. According to the “nobody knows” concept (Havens, 2017), there is inherently high risk in predicting which media goods will be successful. Now success depends on the desires of consumers who are discovering their own creative autonomy.

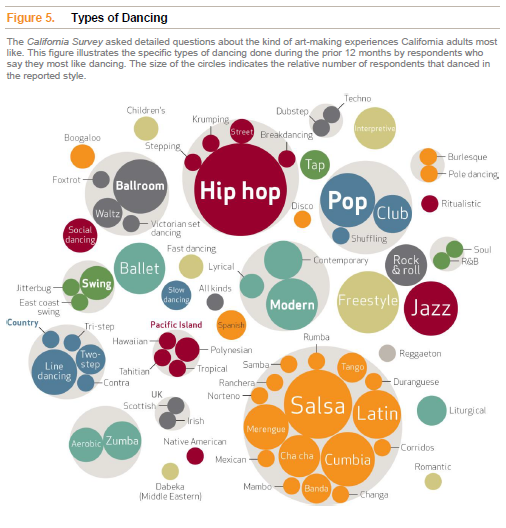

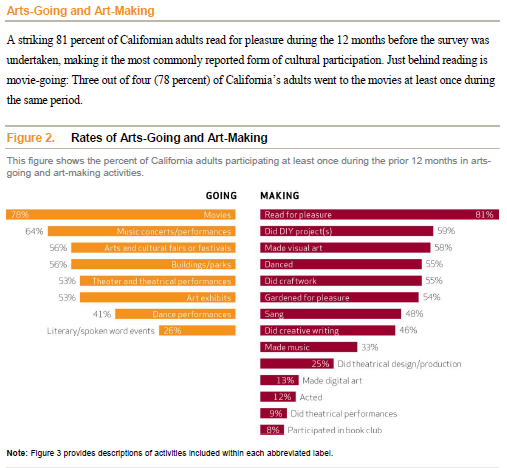

Many have questioned how the creative class will participate within our culture. One study found that the demand for arts and culture is incredibly high and with new technology, the expectations and cultural norms have changed as well. Each consumer is engaging with art in new ways that ultimately show a disparity between traditional cultural programming and curated content for niche genres (Novak-Leonard, 2015). In California people have varied interests, but there are evident patterns of lower cultural participation for members of the largest and growing demographic groups. As “art going” has shifted to “art making” throughout the state of California, it is arguable that this trend may continue to be seen in states across the country.

Figure 3. Classification of Cultural Interests for Californians (Novak, 2015)

Figure 4. Rates of Art-Going vs Art-Making in California (Novak, 2015)

Shifts from “going” to “making” can be seen in new artforms, genres and businesses. In the “do-it-yourself” community there is a rise in cultural participation through meme culture and grass roots production companies. Immersive theatre experiences, like Sleep No More and Too Much Light Makes the Baby Go Blind play to the tendencies of the creative class by providing opportunities for audiences to participate instead of sitting complacently in a dark theater (Greene, 2016). In these new shows, members of the audience are asked to seek out adventure and participate in new ways that engage with creative class workers. Directors and producers are surrendering their creative autonomy in order sell their shows. With this exchange they are selling their curatorial agency to align with the consumer’s creative tendencies.

Another factor comes from digital disruption. Digitization has led to new forms of entertainment curated by and for niche consumers and eventually leading to the formation of “filter bubbles” (Parsier, 2011). Technology has now made it easier than ever to become a producer of your own work and this may create an economy based on individual tastes whether it is considered technological or cultural determinism.

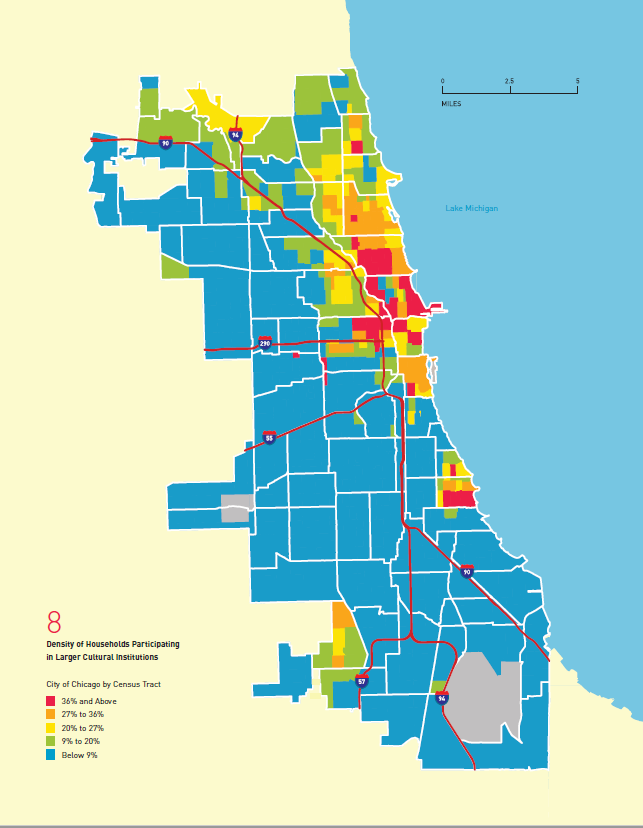

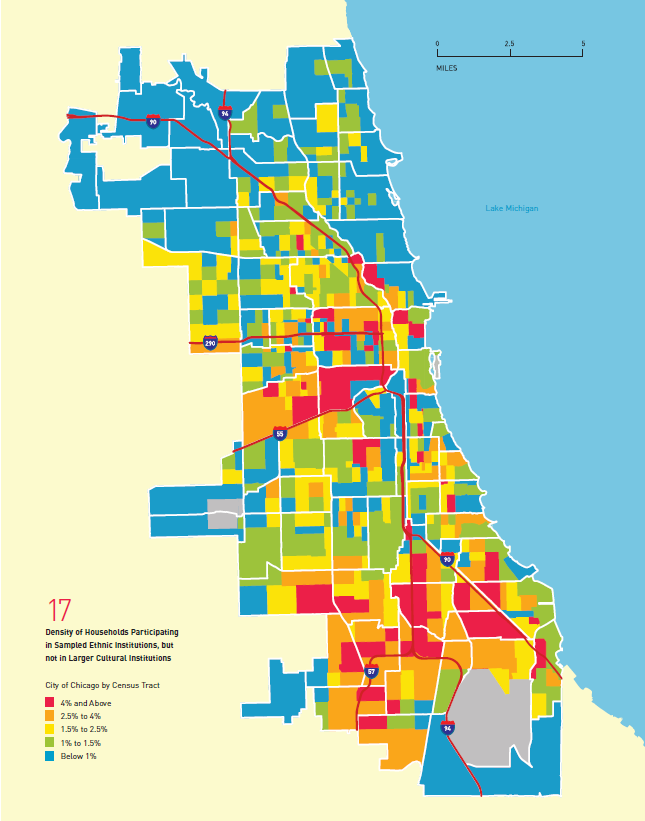

Also, the real audience is now actively being tracked as it shifts away from legacy arts organizations. This shift can be monitored through new cultural engagement studies like Mapping Cultural Participation from the University of Chicago (Lalonde, 2006). Contrary to the current industry lore, the documented agency of prosumers (or casual creatives) emerging from the creative class appear to be disrupting traditional media and entertainment through technology but also through their own geographic engagement within a cultural city.

Figure 5. Cultural participation: Large Cultural Institutions

Figure 6. Cultural participation: Not Large Cultural Institutions

When casual creatives continue making public goods based on their preferences, there could be dangerous consequences. Without a ministry of culture, there is no real curatorial control that will protect our “art for art sake” during this shift. Content regulation may be a good form of equity alongside digital disruption, but ultimately it is the consumers who are deciding what they want. With the lack of power in regulatory agencies such as the National Endowment of the Arts, the control will most likely fall into the hands of corporations, studios and record labels who aim to market each customer based on their preferred content. By leveraging this marketplace of attention, advertisers, producers and consumers volunteer their eyes to participate in “the work of watching” and “the work of being watched” (Smith, 2018). In an endless cycle of gathering user data and marketing niche content specifically for maximum enjoyment, our casual creatives may become bored with curated corporate content and send their expensive music, films and television programming down the long tail for other niche viewers.

It is true that digitization and aggregation of our newly created content has its concerns, but it does also provide opportunities. The rise of the casual creative can lead to convergence and incredible cultural participation. As the creative class continues to grow, we are experiencing what many are calling creative migration (Smith, 2018). Creative workers are now moving to Post-Fordist cities like San Jose, Durham, Chicago, and Washington D.C. This geographic shift is forming new clusters of innovation, design, finance and media that may be attributed to the interests of creative workers. With the rise of digitization, new connections are being formed by using new technology, media product communication systems and incredible cultural innovations. Within the creative class we are likely to find ourselves curating our own lives and working more democratically than ever before.

What can we expect from this new exciting world and what will casual creativity bring for our society? We are experiencing a shift in our cultural preferences. People want to participate with their entertainment in new ways and are developing niche tastes. This change in our cultural landscape has forced curators to develop new forms of entertainment and even caused disruption for legacy entertainment executives; stripping them of curatorial power. Could this be the fall of traditional legacy institutions of the Fordist-era, or is this a new renaissance brought to life by the rise of the creative class? Only you can decide and we all will be there to participate along with you.

Sources:

Andreasen, N. C. (2018, February 14). Secrets of the Creative Brain. Retrieved from

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/07/secrets-of-the-creative-brain/372299/

Brooks, D. (2000). Why bobos rule. Newsweek, 135(14), 62-64.

Bush, G. W. (2017). Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors.

Florida, R., & Safari, an O’Reilly Media Company. (2012). The Rise of the Creative Class—

Revisited (2nd ed.). Basic Books.

Carrns, A. (2017, September 20). A Paintbrush in One Hand, and a Drink in the Other. Retrieved

from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/20/business/smallbusiness/paint-and-sip-classes.html

Cohen, F. (2017, July 13). A Cult Following? My Dad's Garage-Rock Band Nailed It. Retrieved from

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/13/arts/music/rising-storm-calm-before.html

Greene, M. (2016, December 08). End of 'Too Much Light' brings a longtime schism in the Neos out

into the open. Retrieved from https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/theater/news/ct-neofuturist-turmoil-ent-1208-20161207-story.html

Havens, Timothy, and Amanda D. Lotz. Understanding Media Industries. Oxford University Press Inc,

2017.

Huttler, A. (2017, October 30). The Rise of the Casual Creative (Part 1) – Exponential Creativity

Ventures – Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/exponential-creativity/the-rise-of-the-casual-creative-part-1-11aacf943f87

Kennicott, P. (2017, March 12). George W. Bush's best-selling book of paintings shows curiosity and

compassion. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/books/george-w-bushs-best-selling-book-of-paintings-shows-curiosity-and-compassion/2017/03/11/f252174c-05af-11e7-ad5b-d22680e18d10_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.cadd34c0cb48

LaLonde, R. J., O'Muircheartaigh, C. A., Perkins, J., Grams, D., English, E., & Joynes, D. C.

(2006). Mapping cultural participation in Chicago. Cultural Policy Center at the University of Chicago, Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies.

Novak-Leonard, J., Reynolds, M., English, N., & Bradburn, N. (2015). The Cultural Lives of

Californians.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: How the new personalized web is changing what we read and

how we think. Penguin.

Smith, Jacob. “Lectures.” Understanding the Creative Industries. (2018). Evanston, Illinois.

Watts, D. J. (2011). Everything is obvious:* Once you know the answer. Crown Business.