Great Midwestern cities have rich histories full of grit, determination, innovation, and tragedy, all of which come from their diverse communities. According to Deborah Stone, “public policy is about communities trying to achieve something as communities” implying that in order to make changes in communities, it is necessary for the people to contribute in some way (Stone, 2012). Mayor Rahm Emmanuel had a similar realization when he constructed the Chicago Cultural Plan in 2012. In a city with thousands of community assets but a scarcity of civic pride, the goal of the Chicago Cultural Plan was to provide access to arts and culture by focusing on Chicago’s neighborhoods (Emmanuel, 2012). With a staggering inequality between the north, south and west sides of the city, it was necessary to create an event that could bring Chicago’s communities together and express pride in a shared cultural heritage. One recommendation was to link neighborhoods to each other and to downtown by means of a cultural festival on the Chicago River. Answering this call, Redmoon Theater created one of the boldest initiatives in Chicago’s history, the Great Chicago Fire Festival.

Ephemera are things that only exist for a short period of time and, like flames, ephemeral moments can change a place in an instant. Chicago’s history is branded by one of the largest and most damaging fires ever recorded, the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. This event launched the city into a new era of progress and entrepreneurship that has not been surpassed by other great cities. Following the tragic fire, Chicago rebuilt its infrastructure and created what was known as the “white city” for the Chicago World’s Fair. The Great Chicago Fire became a point of pride despite the immense tragedy.

According to Jim Lasko, co-artistic director of Redmoon Theater, ephemera can hold immense power and change the meaning of a place in an instant. Lasko defines this concept as “placemaking” or “meaning + space = place.” He commonly applies this simple equation to such locations as Ground Zero, Sandy Hook, or Hiroshima, explaining that signature events can shift public opinion of what a place means, whether it’s tragic or inspiring (Lasko, 2013). It was Lasko’s belief that cultural placemakers could bring meaning to spaces through altruistic means. Over the course of twenty-five years, Redmoon Theater proved that innovation, collaboration and public storytelling could attract audiences and connect neighborhoods through curated signature events. The company applied its ability to create urban spectacle in public spaces with a highly collaborative process to their work with the city’s Cultural Plan.

In 2013, a year after the Cultural Plan was implemented, Redmoon Theater proposed the Great Chicago Fire Festival. This festival would celebrate each neighborhood and serve as a reminder of the city’s grit and determination, ending with a signature event on the Chicago River. It was meant to bring the city together in a similar way that Mardi Gras does for New Orleans or the “Running of the Bulls” does in Spain. It would be a new tradition that could inspire the city to remain strong together and live like the men and women who came before them.

ArtPlace America embraced this idea and, alongside several foundations and corporate sponsors, awarded Redmoon Theater a project grant for creative placemaking. In collaboration with the City of Chicago: Department of Culture and Special Events (DCASE) and the Chicago Park District, Redmoon began to plan and implement the project (Lasko, 2016). The process began with a collaboration at Chicago’s Night out in the Parks initiative. The program facilitated free performances in each neighborhood. This collaboration allowed Redmoon Theater to begin working with the city and to collect valuable information to determine which initiatives would make the festival, scheduled for October 2014, a success.

Following the summer of 2013, Redmoon held a series of retreats with civic and cultural partners. Throughout the process, Redmoon showed considerable ambition and began promising to deliver a variety of services and initiatives. “Sidewalk Senates” were a series of public events and community arts activities designed to discover and to tell the story of each neighborhood. These were combined with “Pop-Up Tours” (interactive tours led by a local resident, telling stories from a specific ward) and “Chalk Talks” (collaborative public art making and artistic disruption within local neighborhoods).

In early 2014, DCASE requested a second retreat with Redmoon to create a concrete plan for the summer, at which point they decided to combine initiatives into “Summer Celebrations.” These celebrations were made up of “Community Feasts,” two neighborhood barbeques (one at the beginning of the summer and one again at the end) and “Canopy Workshops” (activities helping local artists decorate their own banner and visually representing their ward at the festival). The workshops would feature “Fire Flowers” (pinwheels in the shape of lotus flowers that assemble into a community art piece at the end of the summer) and the construction of the “Cyclone Grill” (a rotating stage that served food alongside disc jockeys).

These initiatives were to be spread across fifteen neighborhoods including, Bronzeville, South Shore, Pilsen, Albany Park, Uptown, Old Town, Roseland, South Chicago, Englewood, Little Village, Avondale, Humboldt Park, Woodlawn, Austin, and North Lawndale. In addition to providing programs in these neighborhoods, Redmoon partnered with DIGITAS, a local marketing firm, and WTTW to help them expand their reach. All these resources eventually went towards the creation of a “Mobile Photo Factory” (a mobile photography station that documents neighborhood stories), a “Neighborhood Bazaar” (a marketplace that represented local artists and businesses) and the “Grand Spectacle” (the lighting of the fire on the Chicago River).

Unfortunately, Redmoon Theater failed to present the “Pop-Up Tours,” “Sidewalk Senates,” “Chalk Talks,” and “Fire Flowers” initiatives, which created a great deal of frustration for local residents and caused a considerable amount of friction within the neighborhood partners. As a result, Redmoon was forced to issue an apology for making promises they could not deliver. The “Canopy Workshops,” “Community Feasts,” and “Mobile Photo Factory” initiatives were realized but were found to be far too mechanical. Many staff members noticed that people went in and out with very little interaction or critical reflection.

This lack of engagement in the neighborhoods may have been a repercussion of Redmoon’s ambitious amount of programming slated for its season. In addition to the Great Chicago Fire Festival the company was producing a full season at their new facility in Pilsen, along with fundraisers and holiday parties at Navy Pier. This overabundance of programming forced the company to consolidate their resources and continually cut back on their community programs. After their second retreat Redmoon focused the remainder of its resources on the “Grand Spectacle” itself. They brought in After School Matters and an army of interns to help build the centerpiece sculptures for the final product, which resembled pre-1871 architecture.

At last October 4th, 2014, the day of the festival had arrived. Redmoon had coordinated choral performances on boats along with several percussionists playing large gongs. There were three large blue buildings, ready to ignite for the “Grand Spectacle,” that floated into position on the river between Navy Pier and Wolfe Point. As the performance moved forward there was a parade of artists engaging with nearly 40,000 people on the riverfront at the “Neighborhood Bazaar.” Everything seemed to be exactly as recommended by Mayor Emmanuel’s Cultural Plan. However, on this cold and damp evening, even with a variety of pyrotechnicians and designers on hand, the buildings did not ignite. The spectacle was only saved by the “Neighborhood Bazaar” selling vast amounts of their wares, the sounds of beautiful music, the visual representation of neighborhood stories on several floating projection screens, and by an expensive firework display.

The public reaction to the Great Chicago Fire Festival was profoundly negative. Nearly every major Chicago newspaper detailed its ineffectiveness and, when the buildings did not ignite, the firefighters on the scene only responded with snarky comments, interspersed with suggestions for the pyrotechnicians (Pratt, 2015). The concept proved to be inequitable and largely inefficient: the audience was disapproving, the work of the fifteen neighborhoods was not represented, the equity of the process was not celebrated, and the fortune of city funding (nearly $350,000) was spent on a failed venture. The focus was diverted away from each neighborhoods’ stories to the eventual closure of Redmoon Theater. After twenty-five years of producing theater in the city, the Great Chicago Fire Festival financially ruined the company. This lack of sustainability proved to be their downfall as the company closed an impossibly expensive season and shut down their enormous warehouse in Pilsen. In their farewell letter to Chicago, they sadly stated that their innovations haven’t been able to keep up with their civic goals (Lulay, 2015). Redmoon managed to repeat the festival one last time on Northerly Island in 2015, but it was without funding from the City of Chicago (Byrne, 2015). Meanwhile, the city began to endorse co-working spaces, such as incubators and accelerators, to stimulate the creative economy.

Was Redmoon Theater’s Great Chicago Fire Festival a true failure? Was its inability to ignite the only memory people will have when regarding this signature event? These questions are imperative when analyzing ephemeral events at large. If Redmoon’s focus was to cultivate civic pride and to represent the underrepresented, this festival was a failure. By not distributing resources equally to each neighborhood, spending most of the year throwing holiday parties and reassessing programming through strategic planning retreats, Redmoon did not act as an agent of representation.

But, while Redmoon did not succeed with this aspect of the Cultural Plan, they did stumble upon something greater in the process – they created a sense of membership. The festival allowed the city to celebrate grit and determination, the cornerstones of Chicago’s civic identity, by convincing neighborhood residents to join the rest of the city at one large spectacle. Everyone had an opportunity to participate and connect with other residents in new ways. Although there are no impacts that are measurable at this point, the model has been created and can be reproduced.

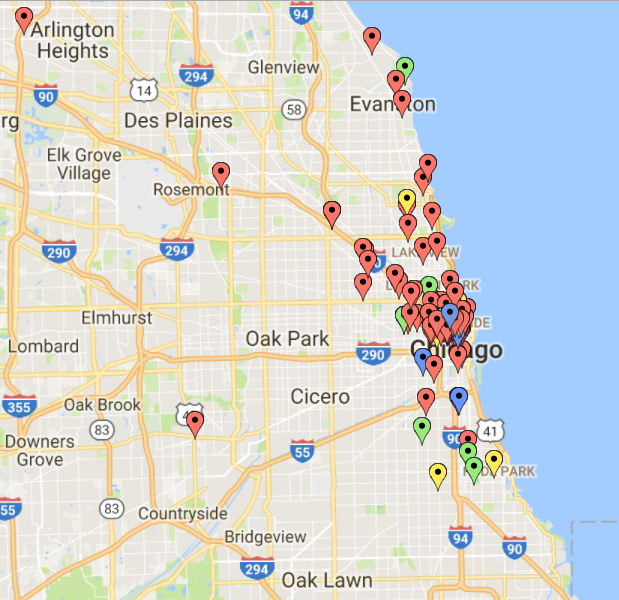

When examining the city’s actions after the failed Great Chicago Fire Festival, it is important to note that the city focused more on lucrative and corporate co-working spaces and less on non-profit community engagement. Accelerators, such as 1871 (named after the Great Chicago Fire), are proving that venture capitalists, creatives and entrepreneurs can create significant impact in communities through technology. Mayor Emmanuel has endorsed several co-working centers, claiming that they are crucial to establishing Chicago as a national leader. This proclamation, much like his endorsement of the Great Chicago Fire Festival, continues to inspire business owners to build more incubators and accelerators across the city and to serve as “Neighborhood Connectors,” or entities that establish partnerships and collaborations across private, public and non-profit sectors (Emmanuel, 2012). As represented in the map below, these co-working spaces tend to remain in the most affluent sections of Chicago, with a few exceptions.