It’s no secret that Lyric Opera audiences have gotten smaller every year. No matter how many catchy phrases they display on the side of their building, the house never feels full enough, and yet, their competition grows every year. As high-brow entertainment continues to be labeled as niche content, many large cultural organizations are experiencing disruption within their industry because of the new advantages that are available for lean start-ups.

Digital technology is now affordable and accessible to anyone, allowing new businesses to pursue leaner business models and create higher quality products. Disruption is inevitable with the development of at-home production software, digital distribution channels, and a “long tail” of aggregated niche content. While large companies struggle to fill seats at the opera, ballet and theater, we are seeing a surge in the DIY art scene because smaller companies can now use services like YouTube, Hootsuite, Google Drive, and Slack to run their businesses remotely. According to the California Survey of Arts & Cultural Participation, “new technology, expectations and cultural norms mean [Californians] engage in art in new ways and places” (Novak-Leonard, 2015). The survey points out that people are moving away from going to concerts, performances and exhibits the way they traditionally did for nearly a century. Instead they are engaging with culture digitally and making creative content on their own based on their personal preferences.

In addition to the use of disruptive technology, the flexibility of smaller organizations has become a destabilizing force for larger arts organizations because of costly overhead. Anthony Freud, general director of Lyric Opera, has admitted that “[Lyric is] rather monolithic in arts organizational terms, in that it has a very large, inflexible overhead that plans four to six years in the future” (DeCastro, 2016). These slow-moving institutions are easily disrupted by nimble storefront organizations that can produce content in half the time at a fraction of the cost. This nimbleness makes it easier to pivot when mistakes are made. To their disadvantage, large institutions are unable to pivot quickly enough to avoid mistakes that “have additional zeros” (Blank & Dorf, 2012). By utilizing independent contractors, unconventional spaces and vast amounts of passionate underemployed independent artists, small arts organizations can use these digital technologies to surpass their competition with well targeted and engaging experiences outside of the opera house.

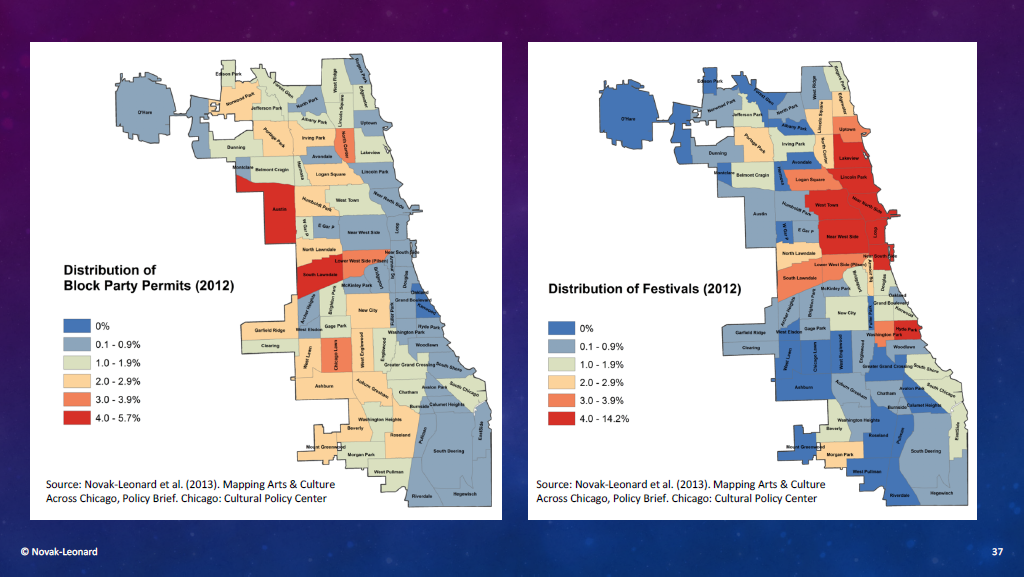

Unfortunately, many large institutions are currently failing to engage with most of the cultural landscape. In Chicago, we’re seeing most top cultural organizations operating solely in the most affluent areas of the city. By comparing block party permits to cultural festivals in Chicago, cultural participation is shifting away from institutions and towards DIY events (Figure 1 & 2, Novak-Leonard, 2013). This past year New York released their first cultural plan, which prioritizes funding for diverse arts organizations (Pogrebin, 2017). This new plan is likely to disrupt institutions like Lincoln Center, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim in the coming years. As the divide continues to grow between institutions and their nimble competitors, it is likely that the more passionate the large organizations are the less likely they are to follow the markets and notice this trend (Latterman, 2018).

(Figure 1 & 2)

As digital disruption continues to affect legacy institutions like Lyric Opera, our cultural landscape is likely to shift in the favor of the next generation artists and producers. Disruption is seen at nearly every level, from sold out concerts playing video game music at Chicago’s Symphony Center to Lindsey Stirling, a hip-hop violinist, building her career on YouTube (Smith, 2017). We are at a moment in history when large cultural institutions may no longer be able to sustain themselves into the future if adjustments are not made to extend their reach or improve their technology.

Sources:

Blank, S. G., & Dorf, B. (2012). The startup owners manual. the step-by-step guide for building a great company. Pescadero, CA: K & S Ranch.

DeCastro, G. (2016, May 06). Panel Navigates the Economic Viability of Opera. Retrieved April 17, 2018, from https://www.chicagomaroon.com/article/2016/5/6/panel-navigates-the- economic-viability-of-opera/

LaLonde, R., et al. (2006). Mapping Cultural Participation in Chicago

Latterman, G. (2018, April 13). PE Class Lecture.

Novak-Leonard, J. et al. (2015). The Cultural Lives of Californians: Insights from the California

Survey of Arts & Cultural Participation. Chicago: NORC.

Novak-Leonard et al. (2013). Mapping Arts & Culture Across Chicago, Policy Brief. Chicago: Cultural Policy Center.

Pogrebin, R. (2017, July 19). De Blasio, With 'Cultural Plan,' Proposes Linking Money to Diversity. Retrieved April 17, 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/19/arts/design/new-york-cultural-plan-museums.html

SMITH, M. D. (2017). STREAMING, SHARING, STEALING: Big data and the future of entertainment. S.l.: MIT PRESS.